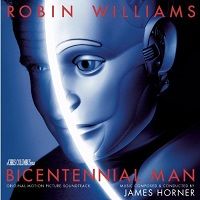

Bicentennial Man soundtrack

By James Southall Saturday May 12, 2018

- Composed by James Horner

- Sony Classical / 66m

Overly mawkish and sentimental, Chris Columbus’s Bicentennial Man isn’t well-remembered. Predicated on an Isaac Asimov story, it follows the story of a robot (Robin Williams) who’s the slave of a wealthy family over a protracted period (along the period is not any surprise to those that know very well what the title means). As time passes he becomes increasingly more human-like also it becomes a tale about precisely how human you need to be before you have human rights. (And he falls in love, needless to say.)

Columbus spent some time working with many great film composers over time, most regularly John Williams – and actually Williams was at one point mounted on this, but dropped out because of presumably-euphemistic “scheduling conflict” (it appears much more likely that his Spidey sense told him this is not likely to be always a great film) – in his absence, Horner was perfect composer-casting because of this. The sprawling timeframe, romantic elements and even the sentimentality are items that attracted him to projects. And taken alone terms, nobody could deny precisely how good his score is – nonetheless it’s possibly the ultimate one where your appreciation depends on your tolerance level for the composer’s well-documented reuse of material, for practically all the major content in the score may also be within others.

It begins having an absolute belter of a track, “THE DEVICE Age”, easily among my favourite individual cues by the composer. A deceptively sweet melody (which continues on to end up being the score’s main theme) ushers us in to the piece before suddenly it goes off in probably the most wonderful direction – the tiny swirling wind motif first found in Sneakers is joined by the “genius theme” piano (also found in Looking for Bobby Fischer and later, perhaps most famously, in A LOVELY Mind). Here it really is joined by metallic, clanging percussion and brass which give it probably the most wonderful sense of motion – also it all leads up to brilliant variant on the James Horner Ending. It’s awesome, it truly is, sending shivers down the spine each time – three . 5 minutes of absolute musical genius.

Slightly disappointingly, good since it is, all of those other score is really nothing beats that. “Special Delivery” opens with a lovely, slightly mysterious melody (recalling Casper in arrangement but I believe in Horner terms the tune actually started back his Star Trek days). In the next 1 / 2 of the piece the wonder becomes more pastoral in nature (The Spitfire Grill, etc). The sense of mystery is back “The Magic Spirit”, accompanied initially by a number of the suspense electronics of Sneakers and Apollo 13, as well as the synth choir that your composer used in a lot of his scores of the period (and that is heard frequently through this score).

“SOMETHING SPECIAL For Little Miss” is quite different, opening with a playful scherzo prior to going by way of a whole host of melodies (including not only this score’s main theme, but additionally The Spitfire Grill‘s). It leads up to delightfully gentle conclusion, with simple harp playing on the synth choir. “Mechanical Love” is really a bit unusual (as, Perhaps, mechanical love will be) – the primary theme is played by keyboard over pizzicato strings plus some odd percussion. Then, “Wearing Clothes for the very first time” is a lot more low-key but does introduce a motif which will go on to be utilized quite often on the remainder of the score, a twinkly piano motif used several times over time by the composer, most famously in Deep Impact.

We arrived at “THE MARRIAGE”… in the event that you’d never heard another score by James Horner but knew how well-regarded he could be, you’d think this must surely be perhaps one of the most wonderful pieces he previously ever written. If the usage of that Deep Impact theme (which dominates the cue’s opening) is really a little offputting… then, following the first really big performance of the score’s love theme – you hear the strings suddenly entering a fairly familiar-sounding group of truly sumptuous harmonies and suddenly, it’s the Princess theme from Braveheart (altered by the end, admittedly) – somehow it appears more egregious compared to the other borrowings, perhaps because it’s among the composer’s most well-known tunes (imagine if John Barry had stuck the James Bond theme in The Ipcress File – it’s that type of thing, really). Anyway, even though your patience isn’t tested by the others, that moment may be a bit much for you personally. Still, like I said, when you can overcome that then it really is genuinely sensationally beautiful.

The lengthy “The Duration of time, A Changing of Seasons” (an antique Horner track title, that) is another gorgeous piece. It opens with the primary theme, performed as usual by winds, switches into the twinkly piano motif, then a protracted riff on the love theme (and much more Braveheart). It’s all very lovely and contains a vintage Horner sweep to it. The primary theme is back again to open “The Seek out Another”, with a driving momentum to it this time around; it leads (since it frequently does in the score’s second half) in to the love theme, which itself leads (since it in the same way frequently does) into Braveheart (possibly the latter two devices are both area of the same thing). And Deep Impact again. “Transformed” is really a bit different from the others, a good, playful piece with some creative usage of synths, before more typical swoony Horner piano writing.

The prevailing emotion in “Emotions” is joy, really, in conjunction with a feeling of discovery that’s quite compelling. Another playful scherzo follows, “A FRESH Nervous System” – Horner didn’t do such light-hearted music frequently, however when he did, he achieved it perfectly. In “A Truer Love”, the orchestra gradually swells and becomes ever-warmer just like the rising sun, prior to the love theme bursts forth in every its glory. Things have a slightly darker turn with a sense of tragedy in the air in “Petition Denied”, and Horner starts taking out all his emotional stops in “AGEING”, a gorgeous undertake the primary theme. The score ends with “The Gift of Mortality”, an excellent summary of the score’s main themes. There’s yet another track on the album, once we’re “treated” to a Celine Dion vocal of the love theme (“YOU THEN Look At Me”) – if the hope was to fully capture lightning in the bottle again, well, it didn’t work. It’s the only real track on the album I don’t like.

I believe I’ve stated before that I’ve long since comprehend James Horner’s self-referencing. Although it sounds pretentious, I must say i do think he approached things as though he was writing some type of great big single work across most of his scores really, and he used to link things together quite deliberately. I could realize why others would just get frustrated by it – and truly, in the event that you’re somebody who does, you need to stay well from Bicentennial Man. Ignoring all that, it truly is a brilliant good article in the event that you just judge it alone merits. As he usually was, Horner was criticised by many for going overly-sentimental along with his music, but in the event that you really give consideration then all that sentiment is merely from the film – although some of it really is undeniably big and lush, there’s an extraordinary lightness-of-touch running right through a surprising quantity of the score which really is a joy – and the melodic content, familiar though it might be, is merely brilliant.

Recent Comments